Clint Eastwood

| Clint Eastwood | |

|---|---|

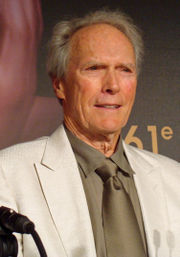

Eastwood in 2008 |

|

| Born | Clinton Eastwood May 31, 1930 San Francisco |

| Occupation | Actor, film director, film producer, composer |

| Years active | 1953–present |

| Spouse | Maggie Johnson (1953–78) Dina Ruiz (1996–present) |

| Partner | Sondra Locke (1975–89) Frances Fisher (1990–95) |

Clinton "Clint" Eastwood (born May 31, 1930) is a renowned American film actor, director, producer and composer. He has received five Academy Awards, five Golden Globe Awards, a Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award, two Cannes Film Festival awards, and five People's Choice Awards — including one for Favorite All-Time Motion Picture Star.[1]

Eastwood is known for his anti-hero acting roles in violent action and western films. Following his six-year run on the television series Rawhide (1958–65), he starred as the Man With No Name in the Dollars Trilogy of Spaghetti Westerns in the 1960s, and as Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films in the 1970s and 1980s. These roles have made him an enduring cultural icon of masculinity.[2] Eastwood is also notable for his comedic efforts in Every Which Way But Loose (1978) and its sequel Any Which Way You Can (1980), his two highest-grossing films after adjustment for inflation. For his work in the films Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004), Eastwood won Academy Awards for Best Director and for producer of the Best Picture, and received nominations for Best Actor. These films in particular, as well as others including Paint Your Wagon (1969), Play Misty for Me (1971), High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Escape from Alcatraz (1979), Pale Rider (1985), In the Line of Fire (1993), and Gran Torino (2008), have all received great critical acclaim and commercial success. He has directed most of his star vehicles as well as films he has not acted in, such as Mystic River (2003) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), for which he received Academy Award nominations.

He also served as the nonpartisan mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California from 1986–1988, tending to support small business interests on the one hand and environmental protection as well.

Contents |

Early life

Clint Eastwood was born in San Francisco to Clinton Eastwood (1906–70), a steelworker and migrant worker, and Margaret Ruth (née Runner; 1909–2006), a factory worker.[3] He was a large baby (11 pounds and 6 ounces; 5.62 kg) and was named "Samson" by the nurses in the hospital.[4][5] Eastwood is of English, Scottish, Dutch, and Irish ancestry,[3][6] and was raised in a "middle class Protestant home".[7] His family relocated often, as his father worked at different jobs along the West Coast, including at a pulp mill.[8][9] The family settled in Piedmont, California, where Eastwood attended Piedmont Junior High School and Piedmont Senior High School. Later he transferred to Oakland Technical High School, where the drama teachers encouraged him to enroll in school plays, but he was not interested. He held a series of jobs as his family moved to different areas, including paper carrier, grocery clerk, forest firefighter, and golf caddy.[10][11]

After graduating from high school in 1949, Eastwood intended to enter Seattle University and major in music theory. However, in 1950 he was drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War.[12] He was stationed at Fort Ord, where his certificate as a lifeguard got him appointed as a life-saving and swimming instructor.[13] He safeguarded film and television actors who had joined the Army through the Special Services program, including John Saxon, David Janssen, and Martin Milner.[14] In 1951, while on leave, Eastwood rode in a Douglas AD bomber that ran out of fuel and crashed in the ocean near Point Reyes.[15][16] After escaping from the sinking fuselage, he and the pilot swam 3 miles (5 km) to the shore.[17]

He later moved to Los Angeles and began a romance with Maggie Johnson, a college student.[18] During this time he managed an apartment house in Beverly Hills by day (into which he moved) and worked at a Signal Oil gas station by night.[19] He enrolled at Los Angeles City College and soon after became engaged to Maggie. They were married shortly before Christmas in 1953 in South Pasadena and honeymooned in Carmel.[19][20]

Film career

1950s

According to the CBS press release for Rawhide, Universal (known then as Universal-International) film company happened to be shooting in Fort Ord and an enterprising assistant spotted Eastwood and invited him to meet the director.[21] However, the key figure, according to his official biography, was a man named Chuck Hill, who was stationed in Fort Ord and had contacts in Hollywood.[21] While in Los Angeles, Hill had become reacquainted with Eastwood and managed to sneak Eastwood into a Universal studio, where he showed him to cameraman Irving Glassberg.[21] Glassberg was impressed with Eastwood's appearance and stature and believed him to be "the sort of good looking young man that has traditionally done well in the movies".[21]

Glassberg arranged for director Arthur Lubin to meet Eastwood at the gas station where he was working in the evenings in Los Angeles.[21] Lubin, like Glassberg, was highly impressed and promptly arranged for Eastwood's first audition. However, he was somewhat less enthusiastic after seeing the audition, remarking, "He was quite amateurish. He didn't know which way to turn or which way to go or do anything".[22] Lubin nevertheless told Eastwood not to give up, suggesting that he attend drama classes, and later arranging for an initial contract for Eastwood in April 1954 at $100 a week.[22] Some people in Hollywood, including Eastwood's wife Maggie, were suspicious of Lubin's intentions. Lubin was homosexual, and he maintained a close friendship with Eastwood in the years that followed.[23] After signing, Eastwood was initially criticised for his speech and awkward manner; he was soft spoken and, when performing in front of people, was cold, stiff, and awkward.[24] Fellow talent school actor John Saxon described Eastwood as "being like a kind of hayseed. Thin, rural, with a prominent Adam's Apple, very laconic and slow speechwise."[25]

In May 1954, Eastwood made his first real audition, trying out for a part in Six Bridges to Cross, a film about the Brinks robbery that would mark the debut of actor Sal Mineo. Director Joseph Pevney was not impressed by Eastwood's acting and rejected him for any role.[25] Later Eastwood tried out for Brigadoon, The Constant Nymph, Bengal Brigade and The Seven Year Itch in May 1954, Sign of the Pagan (June), Smoke Signal (August) and Abbott and Costello Meet the Keystone Kops (September), all without success.[25] He was eventually given a minor role by director Jack Arnold in Revenge of the Creature, a film set in the Amazon jungle, which was the sequel to The Creature from the Black Lagoon, released just months earlier.[26]

In September 1954, Eastwood worked for three weeks on Arthur Lubin's Lady Godiva of Coventry in which he donned a medieval costume, and screen tested for the role with Olive Sturgess,[27] and then in February 1955, won a role playing "Jonesy", a sailor in Francis in the Navy and his salary was raised to $300 a week for the four weeks of shooting.[28] He again appeared in a Jack Arnold film, Tarantula, with a small role as a squadron pilot, again uncredited.[29] In May 1955, Eastwood put four hours work into the film Never Say Goodbye, in which he again plays a white coated technician uttering a single line and again had a minor uncredited role as a ranch hand (his first western film) in August 1955 with Law Man, also known as Stars in the Dust.[30] He gained experience behind the set, watching productions and dubbing and editing sessions of other films at Universal Studios, notably the Montgomery Clift film A Place in the Sun.[30] Universal presented him with his first TV role with a small television debut on NBC's Allen in Movieland on July 2, 1955, starring actors such as Tony Curtis and Benny Goodman.[31] Although his records at Universal revealed his development, Universal terminated his contract on October 23, 1955,[32] leaving Eastwood gutted and blaming casting director Robert Palmer, on whom he would exact revenge years later, when Palmer came looking for employment at his Malpaso Company. Eastwood rejected him.[33]

On the recommendation of Betty Jane Howarth, Eastwood soon joined new publicity representatives, the Marsh Agency, who had represented actors such as Adam West and Richard Long.[23] Although Eastwood's contract with Lubin had ended, he was important in landing Eastwood his biggest role to date; a featured role in the Ginger Rogers–Carol Channing western comedy, The First Traveling Saleslady.[34] Eastwood played a recruitment officer for Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders. He would also play a pilot in another of Lubin's productions, Escapade in Japan and would make several TV appearances under Lubin even into the early 1960s.[34] As Eastwood grew in success, he never spoke to Lubin again until 1992, shortly after winning his Oscar for Unforgiven, when Eastwood promised a lunch that never happened.[34]

Without the Lubin contract in the meantime, however, Eastwood was struggling.[34] He was financially advised by Irving Leonard and, under Leonard's influence, changed talent agencies in rapid succession: the Kumin-Olenick Agency in 1956 and Mitchell Gertz in 1957. He landed a small role as a temperamental army officer for a segment of ABC's Reader's Digest series, broadcast in January 1956, and later that year, a motorcycle gang member on a Highway Patrol episode.[34] In 1957, Eastwood played a cadet who becomes involved in a skiing search and rescue in the 'White Fury' installment of the West Point series. He also appeared in an episode of the prime time series Wagon Train and played a suicidal gold prospector in Death Valley Days.[35] In 1958, he played a Navy lieutenant in a segment of Navy Log and in early 1959 made a notable guest appearance as a cowardly villain, intent on marrying a rich girl for money, in Maverick.[35]

Eastwood was credited for his roles in several more films. He auditioned for the film The Spirit of St. Louis, a Billy Wilder biopic about aviator Charles Lindbergh. He was rejected and the role went to Jimmy Stewart, who put on makeup to make him look younger. He did, however, have a small part as an aviator in the French picture Lafayette Escadrille, and played an ex-renegade in the Confederacy in Ambush at Cimarron Pass, his biggest screen role to date opposite Scott Brady. His part was shot in nine days for Regal Films Inc. Out of frustration, he said after watching it at the premiere, "It was sooo bad. I just kept sinking lower and lower in my seat and just wanted to quit".[36] Around the time the film was released, Eastwood described himself as feeling "really depressed" and regards it as the lowest point in his career and a point when he seriously considered quitting the acting profession.[36]

In 1958, Eastwood learned from Bill Shiffrin that CBS was casting an hour-long Western series and arranged for a screen test. With screenwriter Charles Marquis Warren overlooking, Eastwood had to recite one of Henry Fonda's monologues from the William Wellman western, The Ox-Bow Incident in his audition.[37] A week later, Shiffrin rang Eastwood and informed him he had won the part of Rowdy Yates in Rawhide. He had successfully beaten competition such as Bing Russell and had got the break he had been looking for.[37][38]

Filming began in Arizona in the summer of 1958.[39] Although Eastwood was finally pleased with the direction of his career, he was not especially happy with the nature of his Rowdy Yates character. At this time, Eastwood was almost 30, and Rowdy was too young and too cloddish for Clint to feel comfortable with the part, privately describing Yates as "the idiot of the plains"[40]

It took just three weeks for Rawhide to reach the top 20 in the TV ratings and soon rescheduled the timeslot half an hour earlier from 7.30 -8.30 pm every Friday, guaranteeing more of a family audience.[41] For several years it was a major success, and reached its peak as number 6 in the ratings between October 1960 and April 1961.[41] However, success was not without its price. The Rawhide years (1959-65) were undoubtedly the most grueling of his life, and at first, from July until April, they filmed six days a week for an average of twelve hours a day.[41] Although it never won Emmy stature, Rawhide earned critical acclaim and won the American Heritage Award as the best Western series on TV and it was nominated several times for best episode by the Writer's and Director's Guilds.[41] Despite appearing in all 217 episodes, Eastwood received some criticism during this period and was considered too laid back and lazy by some directors who believed he relied on his looks and just did not work hard enough.[42]

Eastwood appeared in a western comedy series Maverick, in which he fought James Garner in the "Duel at Sundown" episode.[43][44] Although Rawhide continued to attract notable actors such as Lon Chaney, Jr., Mary Astor, Ralph Bellamy, Burgess Meredith, Dean Martin and Barbara Stanwyck, by late 1963 Rawhide was beginning to decline in popularity and lacked freshness in the script was canceled in the middle of the 1965-66 television season.[45]

1960s

In late 1963, an offer was made to Eastwood's co-star Eric Fleming on Rawhide to star in an Italian made western (A Fistful of Dollars), originally named The Magnificent Stranger, to be directed in a remote region of Spain by a relative unknown at the time, Sergio Leone. However, the money was not much, and Fleming, who had always set his sights high on Hollywood stardom, rejected the offer.[46] A variety of actors, including Charles Bronson, Steve Reeves, Richard Harrison, Frank Wolfe, Henry Fonda, James Coburn and Ty Hardin were considered for the main part in the film. Harrison had suggested Clint Eastwood, whom he knew could play a cowboy convincingly.

Through Irving Leonard, the offer was made to Eastwood, who saw it as an opportunity to escape Rawhide and the States and saw it as a paid vacation. He signed the contract for $15,000 in wages for eleven weeks work and which also threw in a bonus of a Mercedes automobile upon completion, and arrived in Rome in May 1964.[47][48] Eastwood was instrumental in creating the Man With No Name character's distinctive visual style that would appear throughout the Dollars trilogy. He had brought with him the black jeans he had purchased from a shop on Hollywood Boulevard which he had bleached out and roughened up, the hat from a Santa Monica wardrobe firm, a leather bracelet and two Indian leather cases with dual serpents,[49][50] and the trademark black cigars came from a Beverly Hills shop, though Eastwood himself is a non-smoker and hated the smell of cigar smoke.[51] Leone decided to use them in the film and heavily emphasised the "look" of the mysterious stranger to appear in the film. Leone commented, "The truth is that I needed a mask more than an actor, and Eastwood at the time only had two facial expressions: one with the hat, and one without it."[50]

"I wanted to play it with an economy of words and create this whole feeling through attitude and movement. It was just the kind of character I had envisioned for a long time, keep to the mystery and allude to what happened in the past. It came about after the frustration of doing Rawhide for so long. I felt the less he said the stronger he became and the more he grew in the imagination of the audience.

The first interiors for the film were shot at the Cinecittà studio on the outskirts of Rome, before quickly moving to a small village in Andalusia, Spain in an area which had also been used for filming Lawrence of Arabia (1962) just a few years earlier.[53] A Fistful of Dollars would become a benchmark in the development of the spaghetti westerns, and Leone would successfully create a new icon of a western hero, depicting a more lawless and desolate world than in traditional westerns. The film made Eastwood into a major film star in Italy.[54] The trilogy would also redefine the stereotypical American image of a western hero and cowboy, creating a character gunslinger and bounty hunter which was more of an antihero than a hero and with a distinct moral ambiguity, unlike traditional heroes of western cinema in the United States such as John Wayne.

Leone hired Eastwood to star in his second film of what would become a trilogy, For a Few Dollars More (1965). Screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni was brought in to write the script which he wrote in nine days; two bounty hunters (Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef) pursuing a drug-addicted criminal (Volontè), planning to rob an impregnable bank.[55] For a Few Dollars More was shot in the spring and summer of 1965 and again interiors of the film were shot at the Cinecittà studio in Rome before they moved to Spain again. Screenwriter Vincenzoni was very important in bringing the films to the states, given that he was fluent in English and accompanied Leone to a cinema in Rome to show the new film after completion to United Artist executives Arthur Krim and Arnold Picker. He sold the rights to the film and the third film (which was yet to be written let alone made) in advance in the states for $900,000, advancing $500,000 up front and the right to half of the profits.[56][57]

In January 1966, Eastwood met with producer Dino De Laurentiis in New York City and agreed to star in a non-Western five-part anthology production named Le streghe or The Witches opposite De Laurentiis' wife, actress Silvana Mangano.[58] Eastwood's nineteen minute installment only took a few days to shoot and was not met well with critics, who described it as "no other performance of his is quite so 'un-Clintlike' ", with the New York Times disparaging it as a "throwaway De Sica".[59]

Two months after his De Sica shoot, Eastwood began working on the third Dollars film, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, in which he again played the mysterious Man With No Name character. Lee Van Cleef was brought in again to play a ruthless fortune seeker, while Eli Wallach, a character actor noted for his appearance in The Magnificent Seven (1960), was hired to play the cunning Mexican bandit "Tuco", although the role was originally written for Volontè, who passed on working with Leone again.[60] The three become involved in a search for a buried cache of confederate gold buried in a cemetery by a man named Jackson, in hiding as Bill Carson. Eastwood was not initially pleased with the script and was concerned he might be upstaged by Wallach, and said to Leone, "In the first film I was alone. In the second, we were two. Here we are three. If it goes on this way, in the next one I will be starring with the American cavalry".[60]

Filming began at the Cinecittà studio in Rome again in mid-May 1966, including the opening scene between Clint and Wallach when The Man With No Name captures Tuco for the first time and sends him to jail.[61] The production then moved on to Spain's plateau region near Burgos in the north, which would double for the extreme deep south of the United States, and again shot the western scenes in Almeria in the south.[62] This time the production required more elaborate sets, including a town under cannon fire, an extensive prison camp and an American Civil War battlefield; and for the climax, several hundred Spanish soldiers were employed to build a cemetery with several thousand grave stones to resemble an ancient Roman circus.[62]

"Westerns. A period gone by, the pioneer, the loner operating by himself, without benefit of society. It usually has something to do with some sort of vengeance; he takes care of the vengeance himself, doesn't call the police. Like Robin Hood. It's the last masculine frontier. Romantic myth. I guess, though it's hard to think about anything romantic today. In a Western you can think, Jesus, there was a time when man was alone, on horseback, out there where man hasn't spoiled the land yet"

The Dollars trilogy was not shown in the United States until 1967. A Fistful of Dollars opened in January, For a Few Dollars More in May and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly in December 1967.[64] The trilogy was publicised as James Bond -type entertainment and all films were successful in American cinemas and turned Eastwood into a major film star in 1967, particularly The Good, the Bad and the Ugly which eventually collected $8 million in rental earnings.[64] However, upon release, all three were generally given bad reviews by critics (despite the select few American critics who had seen the films in Italy previously having a positive outlook) and marked the beginning of Eastwood's battle to win the respect of American film critics.[65] Judith Crist described A Fistful of Dollars as "cheapjack" and believed that "it had nothing on its mind but sadism".[66] Newsweek described For a Few Dollars More as "excruciatingly dopey"[65] and Renata Adler of The New York Times remarked that it was "the most expensive, pious and repellent movie in the history of its peculiar genre".[67] However while Time highlighted the wooden acting, especially Eastwood's, critics such as Vincent Canby and Bosley Crowther of the New York Times were praising of Eastwood's coolness playing the tall, lone stranger;[68] and Leone's unique style of cinematography was widely acclaimed, even by some critics who disliked the acting.[65]

Eastwood spent much of late 1966 and 1967 dubbing for the English-language version of the films and being interviewed, something which left him feeling angry and frustrated.[69] Stardom brought more roles in the "tough guy" mold and Irving Leornard (who would later pass away at Christmas 1969) gave him a script to a new film, the American revisionist western Hang 'Em High, a cross between Rawhide and Leone's westerns, written by Mel Goldberg and produced by Leonard Freeman.[69] Eastwood signed for the film with a salary of $400,000 and 25% of the net earnings to the film, playing the character of Cooper, a man accused by vigilantes of a cow baron's murder and lynched and left for dead and later seeks revenge.[70] With the wealth generated by the Dollars trilogy, Leonard helped set up a new production company for Eastwood, Malpaso Productions, something he had long yearned for and was named after a river on Eastwood's property in Monterey County.[71] Leonard became the company's president and arranged for Hang 'Em High to be a joint production with United Artists.[71] Inger Stevens of The Farmer's Daughter fame was cast to play the role of Rachel Warren with a supporting cast which included Pat Hingle, Dennis Hopper, Ed Begley, Bruce Dern and James MacArthur. Filming began in June 1967 in the Las Cruces area of New Mexico, and additional scenes were shot at White Sands and in the interiors were shot in MGM studios.[72] The film became a major success after release in July 1968 and with an opening day revenue of $5,241 in Baltimore alone, it became the biggest United Artists opening in history, exceeding all of the James Bond films at that time.[73][74] It debuted at number five on Variety's weekly survey of top films and had made its money back within two weeks of screening.[74] It was widely praised by critics including Arthur Winsten of the New York Post who described Hang 'Em High as "A Western of quality, courage, danger and excitement".[75]

Meanwhile, before Hang 'Em High had been released, Eastwood had set to work on Coogan's Bluff, a project which saw him reunite with Universal Studios after an offer of $1 million, more than doubling his previous salary.[74] Jennings Lang was responsible for the deal, a former agent of a director named Don Siegel, a Universal contract director who was invited to direct Eastwood's second major American film. Eastwood was not familiar with Siegel's work but Lang arranged for them to meet at Clint's residence in Carmel. Eastwood had now seen three of Siegel's earlier films and was impressed with his directing and the two became natural friends, forming a close partnership in the years that followed.[76] The idea for Coogan's Bluff originated in early 1967 as a TV series and the first draft was drawn up by Herman Miller and Jack Laird, screenwriters for Rawhide.[77] It is about a character called Sheriff Walt Coogan, a lonely deputy sheriff working in New York City. After Siegel and Eastwood had agreed to work together, Howard Rodman and three other writers were hired to devise a new script as the new team scouted for locations including New York and the Mojave Desert.[76] However, Eastwood surprised the team one day by calling an impromptu meeting and professing that he strongly disliked the script, which by now had gone through seven drafts, preferring Herman Miller's original concept.[76] This experience would also shape Eastwood's distaste for redrafting scripts in his later career.[76] Eastwood and Siegel decided to hire a new writer, Dean Riesner, who had written for Siegel in the Henry Fonda TV film Stranger on the Run some years previously. Don Stroud was cast as the psychopathic criminal Coogan is chasing, Lee J. Cobb as the disagreeable New York City Police Department lieutenant, Susan Clark as a probation officer who falls for Coogan and Tisha Sterling playing the drug addicted lover of Don Stroud's character.[78] Filming began in November 1967 even before the full script had been finalized.[78] The film was controversial for its portrayal of violence,[79][80] but it had launched a collaboration between Eastwood and Siegel that lasted more than ten years, and set the prototype for the macho hero that Eastwood would play in the Dirty Harry films.

Eastwood was paid $850,000 in 1968 for the war epic Where Eagles Dare opposite Richard Burton.[81] However, Eastwood initially expressed that the script drawn up by Alistair Mclean was "terrible" and was "all exposition and complications".[81] The film was about a World War II squad parachuting into a Gestapo stronghold in the mountains, reachable only by cable car, with Burton playing the squad's commander and Eastwood his right-hand man. He was also cast as Two-Face in the Batman television series, but the series was cancelled before he played the part.[82]

In 1969, Eastwood branched out by starring in his only musical, Paint Your Wagon. He and fellow non-singer Lee Marvin played gold miners who share the same wife (played by Jean Seberg). Production for the film was plagued with bad weather and delays and the future of the director's career (Joshua Logan) was in doubt.[83] It was extremely high budget for this period and eventually exceeded $20 million.[83] The film was not a critical or commercial success, although it was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.

1970s

In 1970, Eastwood starred in the western, Two Mules for Sister Sara with Shirley MacLaine. The film, directed by Siegel, is a story about an American mercenary who gets mixed up with a whore disguised as a nun and aids a group of Juarista rebels during the puppet reign of Emperor Maximilian in Mexico.[84][85] The story was initially written by Budd Boetticher, who was later sacked and replaced with Albert Maltz to revise the script.[86] The film saw Eastwood embody the tall mysterious stranger once more, unshaven, wearing a serape-like vest and smoking a cigar and the film score was composed by Morricone.[87] However, although the film also had Leonesque dirty Hispanic villains, the film was considerably less crude and more sardonic than those of Leone.[88] The film, which took four months to shoot and cost around $4 million to make,[89] received moderate reviews, and Roger Greenspun of the New York Times reported, "I'm not sure it is a great movie, but it is very good and it stays and grows on the mind the way only movies of exceptional narrative intelligence do".[90] Stanley Kauffmann described the film as "an attempt to keep old Hollywood alive- a place where nuns can turn out to be disguised whores, where heroes can always have a stick of dynamite under their vests, where every story has not one but two cute finishes. It's kind of The African Queen gone west".[91][92] The New York Times in its book, The New York Times Guide to the Best 1000 Movies Ever Made included Two Mules for Sister Sara in its top 1000 films of all time.[93]

Later in 1970, Eastwood appeared in the World War II movie, Kelly's Heroes with Donald Sutherland and Telly Savalas. The film, which stars Eastwood as one of a group of Americans who steal a fortune in bullion from the Nazis, combined tough-guy action with offbeat humor. It was the last non-Malpaso film that Clint agreed to appear in.[94] The filming commenced in July 1969 and was shot on location in Yugoslavia and London.[89] Directed by Brian G. Hutton, the film involved hundreds of extras and dangerous special effects. The climax to the film echoes that of his Dollars films when he advances in lockstep on a German tiger tank on the street of a small European town, with a Morricone-esque soundtrack by Lalo Schifrin.[89] The film received mostly a positive reception and its anti-war sentiments were recognized.[94] The film has a respectable 83% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[95]

"Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino play losers very well. But my audience like to be in there vicariously with a winner. That isn't always popular with critics. My characters have sensitivity and vulnerabilities, but they're still winners. I don't pretend to understand losers. When I read a script about a loser I think of people in life who are losers and they seem to want it that way. It's a compulsive philosophy with them. Winners tell themselves, I'm as bright as the next person. I can do it. Nothing can stop me."

In the winter of 1969–70, Eastwood and Siegel began planning his next film, The Beguiled. Jennings Lang was inspired by the 1966 novel by Thomas Cullinan and in passing the book to Eastwood he was engrossed throughout the night in reading the tale of a wounded Union soldier held captive by the sexually repressed matron of a southern girls' school.[97] This was the first of several films where Eastwood has agreed to storylines where he is the centre of female attention, including minors.[97] The film, according to Siegel, deals with the themes of sex, violence and vengeance and was based on "the basic desire of women to castrate men".[98] The film later received major recognition in France and is considered one of Eastwood's finest works by the French.[99] However, although the film reached number two on Variety's chart of top grossing films, it was poorly marketed and in the end grossed less than $1 million. According to Eastwood and Jennings Lang, the film, aside from being poorly publicized, flopped due to Clint being "emasculated in the film".[96]

1971 proved to be a professional turning point in Eastwood's career.[100] Before Irving Leonard had died, the last film they had discussed at Malpaso was to give Eastwood the artistic control that he desired and make his directorial debut in Play Misty for Me.[101] The script was originally thought of by Jo Heims, about a jazz disc jockey named Dave (Eastwood) who has a casual affair with Evelyn (Jessica Walter), one of his listeners who had been calling the radio station repeatedly at night asking him to play her favourite song, Erroll Garner's Misty. When Dave ends their relationship the female fan becomes possessive and then violent, turning into a crazed murderess.[102] Filming commenced in Monterey in September 1970, with Eastwood obtaining the rights to Misty after meeting Garner at the Concord Music Festival in 1970 and paying $2,000 for the use of the song The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face by Roberta Flack.[103] The film was highly acclaimed by critics, with critics such as Jay Cocks in Time, Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice and Archer Winsten in the New York Post all praising Eastwood's directorial skills and the film, including his performance in the scenes with Walter.[104]

The script to Dirty Harry was originally written by Harry Julian Fink and Rita M. Fink, a story about a hard-edged New York City (later changed to San Francisco) police inspector Harry Callahan, determined to stop a psychotic killer by any means at his disposal.[105] Dirty Harry is arguably Eastwood's most memorable character and the lines that Callahan utters when addressing a wounded bank robber are often cited amongst the most memorable in cinematic history (see box). The film has been credited with inventing the "loose-cannon cop genre" that is imitated to this day. Eastwood's tough, no-nonsense portrayal of Dirty Harry touched a cultural nerve with many who were fed up with crime in the streets and at a time when there were prevalent reports of local and federal police committing atrocities and overstepping their authority by entrapment and obstruction of justice.[106] Dirty Harry marked the beginning of Eastwood's work with legendary film poster designer Bill Gold. Gold designed (and often photographed) posters for 35 Clint Eastwood films, from Dirty Harry to Million Dollar Baby (2004). After release in December 1971, Dirty Harry proved a phenomenal success which would be go on to become Siegel's highest grossing film and the start of a series of films which is arguably Eastwood's signature role, with fans demanding more. Although a number of critics such as Jay Cocks of Time praised his performance as Dirty Harry, describing him as "giving his best performance so far, tense, tough, full of implicit identification with his character",[107] the film was widely criticized and accused of fascism through Eastwood's portrayal of the ruthless cop. Feminists in particular were outraged by the film and at the Oscars for 1971 protested outside holding up banners which read messages such as "Dirty Harry is a Rotten Pig".[108]

"I know what you're thinking — 'Did he fire six shots or only five?' Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I've kinda lost track myself. But, being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?"

Eastwood next starred in the loner Western Joe Kidd, released in 1972. Originally called The Sinola Courthouse Raid, it was about a character inspired by Reies Lopez Tijerina, an ardent supporter of Robert F. Kennedy, known for storming a courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico in an incident in June 1967, taking hostages and demanding that the Hispanic people be granted their ancestral lands back to them. Under the director's helm of John Sturges, who had directed acclaimed westerns such as The Magnificent Seven (1960), filming began in Old Tucson in November 1971, overlapping with another film production, John Huston's The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which was just wrapping up shooting.[109] Outdoor sequences to the film were shot near June Lake, east of the Yosemite National Park.[109]

"I think it is a very good performance in context. Like so many Western heroes, Joe Kidd figures even in his own time as an anachronism—powerful through his instincts mainly, and through the ability of everybody else, whether in rage or gratitude, to recognize in him a quality that must be called virtue. The great value of Clint Eastwood in such a position is that he guards his virtue very cannily, and in the society of "Joe Kidd," where the men still manage to tip their hats to the ladies, but just barely, all the Eastwood effects and mannerisms suggest a carefully preserved authenticity."

Eastwood was also far from in perfect health during the film and suffered symptoms that relayed the possibility of a bronchial infection and suffered several panic attacks, falsely reported in the media as him having an allergy to horses.[111] Joe Kidd received a mixed reception. For instance Roger Greenspun of The New York Times thought the film overall was nothing remarkable and had foolish symbolism and what he suspected was sloppy editing, but praised Eastwood's performance (see box).

1973 proved another benchmark to Eastwood when he directed his first western, High Plains Drifter. It involves the story of a tall, mysterious stranger arriving in a brooding Western town where the people share a guilty secret. They hire the stranger to defend the town against three felons soon to be released but fail to recognise that they once killed this stranger in a brutal whipping and that his reappearance is supernatural. The ghostly stranger forces the people to paint the town red and names it "Hell" and seeks revenge. Holes in the plot were filled in with black humor and allegory, influenced by Sergio Leone.[112] There was some confusion amongst critics and viewers of the film as to whether the avenging character was actually the ghost of the murdered sheriff or a sibling; according to Eastwood he played him as a brother. John Wayne was offered a role in the film and was sent the script, but replied to Eastwood some weeks after the film was released, expressing disapproval, saying that "the townspeople did not represent the true spirit of the American pioneer, the spirit that made America great.[113] The revisionist film received a mixed reception from critics but was a major box office success. A number of critics thought Eastwood's directing was as a derivative as it was expressive with Arthur Knight in Saturday Review remarking that Clint had "absorbed the approaches of Siegel and Leone and fused them with his own paranoid vision of society".[114] Jon Landau of Rolling Stone concurred, remarking that it is his thematic shallowness and verbal archness which is where the film fell apart, yet he expressed approval of the dramatic scenery and cinematography.[114]

Eastwood turned his attention towards a script written by Jo Heims about a love blossoming between a middle-aged man and a teenage girl, Breezy. During casting for the film, Eastwood met Sondra Locke for the first time, an actress who would play a major role in many of his films for the next ten years and an important figure in his life.[115] However, Locke, who was 26 at this time was considered too old for the Breezy part and after much auditioning, a young dark-haired actress named Kay Lenz, who had recently appeared in American Graffiti, was cast. Filming for Breezy began in the November of 1972 in Los Angeles. With Surtees occupied elsewhere, Frank Stanley was brought in the shoot the picture, the first of four films he would shoot for Malpaso.[116] The film was shot very quickly and efficiently and in the end went $1 million under budget and finished three days before schedule.[116] The film was not a major critical or commercial success, it barely reached the Top 50 before disappearing and was only made available on video in 1998.[117]

After the filming of Breezy had finished, Warner Brothers announced that Eastwood had agreed to reprise his role as Detective Harry Callahan in a sequel to Dirty Harry, running under the title, Vigilance but later changed to Magnum Force given its gun theme. Writer John Milius came up with a storyline in which a group of rogue young officers in the San Francisco Police Force systematically exterminate the city's worst criminals, portraying the idea that there are worse cops than Dirty Harry.[118] During filming Eastwood encountered numerous disputes with director Ted Post, scarring their relationship for several years.[119] Although the film was a major success after release, grossing $58.1 million in the United States alone, a new record for Eastwood, it was not a critical success.[120][121] New York Times critics such as Nora Sayre criticized the often contradictory moral themes of the film and Frank Rich believed it "was the same old stuff".[121] In 1974, Eastwood teamed with Jeff Bridges in the buddy action caper Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. The film is a road movie about a veteran bank robber Thunderbolt (Eastwood) who teams with a young con man drifter, Lightfoot (Bridges) who try to stay ahead of the vengeful ex-members of his gang (George Kennedy and Geoffrey Lewis) in the search for a cash deposit abandoned from an old heist. Shot in Great Falls area of Montana, filming for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was shot between July and September 1973.[122] On release in spring 1974, the film was praised for its offbeat comedy mixed with high suspense and tragedy and Eastwood's acting performance was noted by critics but was overshadowed by Jeff Bridges who stole the show in his performance as Lightfoot. When Bridges was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, Eastwood was reportedly fuming at his own lack of Academy Award recognition.[123] Despite critical acclaim, however, the film was only a modest success at the box office, earning $32.4 million.[124] Eastwood was unhappy with the way that United Artists had produced the film and swore "he would never work for United Artists again", and the scheduled two film deal between Malpaso and UA was cancelled.[124]

The Eiger Sanction was based on a critically acclaimed spy novel by Trevanian. The rights to the film were bought by Universal as early as 1972, soon after the book was published, and was originally a Richard Zanuck and David Brown production.[124] Paul Newman was intended to the role of Jonathan Hemlock (Eastwood), an assassin turned college art professor who decides to return to his former profession for one last sanction in return for a rare Picasso painting; he must climb the Eiger face in Switzerland and perform the deed under perilous conditions. After reading the script, Newman declined, because he believed the film was too violent.[124] Mike Hoover, an Academy Award nominated professional mountaineer from Jackson, Wyoming was hired to serve as a mountaineering cinematographer and technical adviser during the shoot. He taught Eastwood how to climb over some weeks of preparation in the summer of 1974 in Yosemite.[125] Filming commenced in Grindelwald, Switzerland on August 12, 1974 with an extensive team of professional climbing experts and advisers on board from America, England, Germany, Switzerland and Canada.[126] Despite prior warnings of the perils of the Eiger, the filming crew suffered a number of accidents.[127] A 27-year old English climber David Knowles, who was acting as body double and photographer was tragically killed during filming, with Hoover narrowly escaping.[128] Eastwood continued to insist on doing all his own climbing and stunts, despite potentially being just seconds from instant death. Upon its release in May 1975, The Eiger Sanction was a commercial failure, receiving only $23.8 million at the box office and was panned by most critics,[129] with Joy Gould Boyum of the Wall Street Journal remarking that, "the film situates villainy in homosexuals, and physically disabled men", dismissing it as "brutal fantasy".[129][130] Eastwood blamed Universal Studios for the films poor promotion and turned his back on them, forming a long-lasting agreement with Warner Brothers through Frank Wells that would transcend over 35 years of cinema and remain intact to this day.[131]

The story to The Outlaw Josey Wales was inspired by a 1972 novel by an apparent Native Indian uneducated writer Forrest Carter, originally titled Gone to Texas and later retitled The Rebel Outlaw:Josey Wales. Later it would be revealed that Forrest Carter's identity was fake, and that the real author was Asa Carter, a onetime racist and supporter of Ku Klux Klan school of politics.[132] It would be a Western, and the lead character, Josey Wales, is a rebel southerner who refuses to surrender his arms after the American Civil War and is chased across the old southwest by a group of enforcers. The characters of Wales, the Cherokee chief, Navajo squaw and the old settler woman and her daughter all appeared in the novel.[133] Director Philip Kaufman cast Chief Dan George, who had been nominated for an Academy Award for Supporting Actor in Little Big Man as the old Cherokee Lone Watie. Sondra Locke, also a previous Academy Award nominee was cast by Eastwood against Kaufman's wishes,[134] as the daughter of the old settler woman, Laura Lee. This marked the beginning of a close relationship between Eastwood and Locke that would last six films and the beginning of a raging romance that would last into the late 1980s. The film also featured his real-life seven-year old son Kyle Eastwood.

Principal photography for The Outlaw Josey Wales began in mid-October 1975.[134] A rift between Eastwood and Kaufman developed during the filming and soon after filming moved to Kanab, Utah on October 24, 1975, Kaufman was notoriously fired under Eastwood's command by producer Bob Daley.[135] The sacking caused an outrage amongst the Directors Guild of America and other important Hollywood executives and resulted in a fine, reported to be around $60,000 for the violation.[135] It resulted in the Director's Guild passing new legislation which reserved the right to impose a major fine on a producer for discharging a director and replacing him with himself.[135] From then on the film was directed by Eastwood himself with Daley second in command, but with Kaufman's planning already in place, the team were able to finish making the film efficiently.

"Eastwood is such a taciturn and action-oriented performer that it's easy to overlook the fact that he directs many of his movies – and many of the best, most intelligent ones. Here, with the moody, gloomily beautiful, photography of Bruce Surtees, he creates a magnificent Western feeling"

Upon release in August 1976, The Outlaw Josey Wales was widely acclaimed by critics. Many critics and viewers saw Eastwood's role as an iconic one, relating it with much of America's ancestral past and the destiny of the nation after the American Civil War.[137] The film was pre-screened at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities in Idaho in a six-day conference entitled, Western Movies:Myths and Images and attended by some two hundred esteemed film critics, academics and directors. The film would later appear in Time magazines Top 10 films of the year.[138] Roger Ebert compared the nature and vulnerability of Eastwood's portrayal of Josey Wales with his Man With No Name character in his Dollars westerns and praised the atmosphere of the film. The film is seen by many as a Western masterpiece and has been awarded a 97% rating on the critical website Rotten Tomatoes.

After The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood was offered the role of Benjamin L. Willard in Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now but declined as he did not want to spend weeks in the Philippines shooting it.[139] He was also offered the part of a platoon leader in Ted Post's Vietnam War film, Go Tell the Spartans. Eastwood refused the part and Burt Lancaster played the character instead.[139] In the end it was decided to make a third Dirty Harry film, The Enforcer. The script, devised by Stirling Silliphant had Harry up against a San Francisco Bay area Symbionese Liberation Army type group, which in real life had terrorized the area in 1974 with ruthless kidnappings and violence, and the film would end in a shoot out at the gang's hideout on Alcatraz island.[140] Eastwood met Silliphant in a restaurant in Tiburon and instantly took a liking to the script, particularly the shoot out and the idea of Callahan having a woman as a police partner, his worst nightmare, a relationship which would gradually blossom during the course of the film and provide a backbone to the film's structure as they encounter different situations, from initial hatred to a fondness of each other and Callahan's genuine sorrow on her being shot in the finale.[141] Tyne Daly, who got the part of the female cop, was given considerable leeway in the development of her character, although after seeing the film at the premiere was horrified by the extent of the violence.[142][143]

With James Fargo to direct, filming commenced in the San Francisco Bay area in the summer of 1976. The film ended up considerably shorter than the previous Dirty Harry films, and was cut to 95 minutes.[144] Upon release in the fall of 1976, The Enforcer was a major commercial success and grossed a total of $100 million, $60 million in the United States and easily became Eastwood's best selling film to date,[143] earning more than some of his previous films combined. However, critically, Eastwood's performance was poorly received and was named "Worst Actor of the Year" by the Harvard Lampoon and the film was criticized for its level of violence.[143] His performance in the third installment was overshadowed by positive reviews given to Daly in her convincing role as the strong-minded female cop.[144]

In 1977, Eastwood directed and starred in The Gauntlet, in which he played a down-and-out cop who falls in love with a prostitute whom he's assigned to escort from Las Vegas to Phoenix in order for her to testify against the mob. Written by Dennis Shryack and Michal Butler, Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand were originally cast as the film's stars.[145] However, fighting between the two forced them to drop out of the project, with Eastwood and Locke replacing them. References to political corruption and organized crime were depicted in the film. Although a moderate hit with the viewing public, critics were mixed about the film, with many believing it was overly violent. Eastwood's long time nemesis Pauline Kael called it "a tale varnished with foul language and garnished with violence". Roger Ebert, on the other hand, gave it three stars and called it "...classic Clint Eastwood: fast, furious, and funny."[146] David Ansen of Newsweek wrote, "You don't believe a minute of it, but at the end of the quest, it's hard not to chuckle and cheer".[140] In 1978, Eastwood starred in Every Which Way but Loose an uncharacteristic, offbeat comedy role. Eastwood played Philo Beddoe, a trucker and brawler who roamed the American West, searching for a lost love, while accompanying his best brother/manager Orville and his pet orangutan, Clyde. An orangutan named Manis was brought in to play Clyde, Geoffrey Lewis as the dimwitted Orville, Beverly D'Angelo as Orville's girlfriend and Sondra Locke as Lynn Halsey-Taylor, the country and western barroom singer. Upon its release, the film was a surprising success and became Eastwood's most commercially successful film at the time and ranks high amongst those of his career to date, becoming the second-highest grossing film of the year.[147] However, it was panned by the critics, with Variety commenting that, "This film is so awful it's almost as if Eastwood is using it to find out how far he can go—how bad a film he can associate himself with". David Ansen of Newsweek described the film as, "plotless junk heap of moronic gags, sour romance and fatuous fisticuffs.[147]

.jpg)

In 1979, Eastwood starred in the fact-based movie Escape from Alcatraz, based on the true story of Frank Lee Morris, who, along with John and Clarence Anglin escaped from the notorious Alcatraz prison in 1962. The inmates dug through the walls with their spoons, made papier-mache dummies as decoys and made a raft out of raincoats and escaped across San Francisco Bay, never to be seen again. The script to the film was written by Richard Tuggle, based on the 1963 non-fiction account by J. Campbell Bruce.[148] Eastwood was drawn to the role as ringleader Frank Morris and agreed to star, providing Don Siegel directed under the Malpaso banner. However, Siegel inisted that it be a Don Siegel film and out-maneouvered Clint by purchasing the rights to the film for $100,000. This created a rift between the friends, causing Siegel to depart to Paramount, a rival studio.[148] Although their disagreement was later patched up and Siegel agreed for it to be a Malpaso-Siegel production, Siegel would never direct an Eastwood picture again. As Siegel and Tuggle worked on the script, the producers paid $500,000 to restore the decaying prison and recreate the cold atmosphere, although some interiors had to be recreated within the studio. The film was a major success, earning $34 million in the states alone and was widely acclaimed by critics, marking the beginning of a newly found critical praise Eastwood began to receive in the early 1980s. Frank Rich of Time described the film as "cool, cinematic grace", whilst Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic called it "crystalline cinema".[149]

1980s

In 1980, Eastwood directed and played the main attraction in a traveling Wild West Show in the comedy film, Bronco Billy. His children Kyle and Alison had small roles as orphans.[150] Eastwood starred alongside Locke, Scatman Crothers, Sam Bottoms, Dan Vadis, Sierra Pecheur and Geoff Lewis.[151] FIlming commenced on October 1, 1979 in the Boise, Idaho area and was shot in five and a half weeks on a low budget of $5 million, two-four weeks before schedule.[152][153] Eastwood has cited Bronco Billy as being one of the most affable shoots of his entire career, and biographer Richard Schickel has argued that the character of Bronco Billy is his most self-referential work.[154][155] The film was a commercial failure,[156] was but appreciated by critics with Kenneth Turan of New West saying, "it shows enough class to rank as the unexpected joy of the season".[157] Janet Maslin of The New York Times believed the film was "the best and funniest Clint Eastwood movie in quite a while", praising Eastwood's directing and the way he intricately juxtaposes the old West and the new.[158] Later in 1980, he reprised his role in the sequel to Every Which Way But Loose entitled Any Which Way You Can. The film received a number of bad reviews from critics, although Janet Maslin of the New York Times described it as, "funnier and even better than its predescessor".[156] The film, however, became another box-office success and was among the top five highest-grossing films of the year.

In 1982, Eastwood directed and starred in Honkytonk Man, based on the novel by Clancy Carlile about an aspiring country music singer named Red Stovall, set during the Great Depression. The script was adapted slightly from the novel; the scene in the novel of where Red gives a reefer to his fourteen-year old son (played by real-life son Kyle) was not approved by Eastwood and altered and the ending was also changed to the playing on the radio of a song written by Red on his death bed, shortly before his burial.[159] The film was shot in the summer of 1982 within six weeks.[160] The first part of the movie was filmed in Bird's Landing, California, although the majority of this feature was filmed in and around Calaveras County, east of Stockton, California. Exterior scenes include Main Street, Mountain Ranch; Main Street, Sheepranch; and the Pioneer Hotel in Sheepranch. Extras were locally hired and many of the towns residents are seen in the movie. The film received a mixed reception upon release, although its has a high score of 93% on Rotten Tomatoes. In 1982, Eastwood also directed, produced and starred in the Cold War-themed Firefox, based on a 1977 novel with the same name by British novelist Craig Thomas. Firefox is an espionage thriller, about a retired Air Force Special Forces Expert, recruited to steal a Soviet supersonic war plane from Moscow. Russian filming locations were not possible due to the Cold War, and much footage was shot at the Thule Air Base in Greenland and in Austria to simulate many of the Eurasian story locations.[161] The film was actually shot before Honkeytonk Man but was released after it.

The fourth Dirty Harry film Sudden Impact (1983), is widely considered to be the darkest, "dirtiest" and most violent film of the series. This would be the last time he starred in a film with frequent leading lady Sondra Locke. The script, written by Joseph Stinson, is about a woman (Locke) who avenges the rape of herself and her sister (now a vegetable) by a ruthless gang at a fairground. The woman systematically murders her rapists one by one, shooting them once in the genitals and once in the head. Pat Hingle and Bradford Dillman also starred alongside Eastwood and footage was shot in the spring and early summer of 1983. The line, "Go ahead, make my day", uttered by Eastwood during an earlier scene in which his regular morning cafe is threatened by robbers, is often cited as one of cinema's immortal lines and was famously referenced by President Ronald Reagan in his campaigns. The film was the highest earning of all the Dirty Harry films, earning $70 million and received rave reviews, with many critics praising the feminist aspects of the film through its explorations of the physical and psychological consequences of rape.[162]

In 1984, Eastwood starred in the provocative thriller Tightrope, inspired by newspaper articles about an elusive Bay Area rapist. Set in New Orleans (to avoid confusion with the Dirty Harry films),[163] Eastwood starred as a single-father cop in a mid-life crisis, lured by the promise of kinky sex. The film explored the way his character is drawn into the killer's tortured psychology and fascination for sadomasochism.[164] Complicating matters are his struggle to single-handedly raise two young daughters (one of which was his real daughter Alison), a growing relationship with a tough rape prevention officer played by Geneviève Bujold, and the troubling thought that the killer shares his own sexual preferences (bondage, masochism, etc.).[165] During filming, Eastwood had an affair with the first murder victim in the film, Jamie Rose.[166] Pierre Rissient arranged for the film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, but failed to win any awards. It opened in 1535 theatres in the summer of 1984 and earned record takings in the first ten days, eventually earnings revenues of $70 million domestically.[167] The film was also a critical success, with J. Hoberman in the Village Voice describing Clint as " one of the most masterful under-actors in American movies" and David Denby commenting that he has become a "very troubled movie icon".[168][169] Others such as Jack Kroll of Newsweek noted the sexuality of the film and vulnerability of Eastwood's character, remarking, "He gets better as he gets older; he seems to be creating new nuances".[170]

Eastwood next starred in the period comedy City Heat (1984) with Burt Reynolds. The film was initially running under the title, Kansas City Jazz under the directorship of Blake Edwards. The film is about a private eye and his partner mixed up with gangsters in the prohibition era in the 1930s. During filming, Eastwood conflicted with Edwards and producer Tony Adams, stipulating "creative differences" as the reason, leading to Edward's replacement with Richard Benjamin.[167] Principal photography began in May 1984 and the film was released in North America in December 1984, grossing around $50 million domestically.

In 1985, Eastwood made his only foray into TV direction to date with the Amazing Stories episode Vanessa In The Garden, starring Harvey Keitel and Sondra Locke; this was his first collaboration with writer/executive producer Steven Spielberg (Spielberg later produced Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima[171]). Eastwood revisited the western genre, directing and starring in Pale Rider. The film is based on the classic Western Shane (1953); a preachers descends magically from the mists of the Sierras and takes the side of the placer miners amidst the California Gold Rush of 1850.[172] The ending is also similar, but the story is told from the girl's viewpoint (Megan) and explores the psychosexual and psychospiritual bridge between childhood and womanhood as both mother and daughter compete for the preacher's affections. The film also bears similarities to Eastwood's previous Man with No Name character, and his 1973 western High Plains Drifter in its themes of morality and justice and exploration of the supernatural. The title is a reference to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as the rider of a pale horse is Death, cited in Revelations Chapter 6, Verse 8.[173] It was primarily filmed in the Boulder Mountains and the SNRA in central Idaho, just north of Sun Valley in late 1984. The opening credits scene featured the jagged Sawtooth Mountains south of Stanley. Train-station scenes were filmed in Tuolumne County, California, near Jamestown. Scenes of a more established Gold Rush town (in which Eastwood's character picks up his pistol at a Wells Fargo office) were filmed in the real Gold Rush town of Columbia, also in Tuolumne County, California. The film also featured Michael Moriarty, Carrie Snodgress, Christopher Penn, Richard Dysart, Sydney Penny, Richard Kiel, Doug McGrath and John Russell. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, but was not a success there, given that international critics believed the film to be too overtly commercial for the festival.[174] Nevertheless, Pale Rider became one of Eastwood's most successful films to date in the eyes of critics, earning him the wide critical acclaim he had sought for so long. Jeffrey Lyons of Sneak Previews said, "Easily one of the best films of the year, and one of the best westerns in a long, long time". Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune said, "This year (1985) will go down in film history as the moment Clint Eastwood finally earned respect as an artist".[175]

In 1986, Eastwood starred in the military drama Heartbreak Ridge, about the 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada, West Indies, with a portion of the movie filmed on the island itself. It co-starred Marsha Mason. However, the title comes from the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge in the Korean War, based around Eastwood's character of Tom Highway, an ageing United States Marine Gunnery Sergeant and Korean War veteran, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions there. Eastwood incorporated more scenes of action and comedy into the film than was initially intended by the original drafter, James Carabatsos, and worked hard with Megan Rose to revise it.[176] Eastwood and producer Fritz Manes meanwhile, intent on making the film realistic, visited the Pentagon and various air bases to request assistance and approval.[177] The U.S. army refused to help, due to Highway being portrayed as a hard drinker, divorced from his wife, and using unapproved motivational methods to his troops, an image the army did not want. They informed the production team that the characterisation lacked credibility and that Eastwood's character was an outdated stereotype and that he was too old for the role.[178] They instead approached the United States Marine Corps, and Lieutenant Colonel Fred Peck was hired as a spokesman for the military during filming and to guide Eastwood's team to making the characters and scenes more realistic. The production and filming of Heartbreak Ridge was marred by internal disagreements, between Eastwood and long term friend Fritz Manes who was producing it and between Eastwood and the DOD who expressed contempt at the film.[178][179] During the film, Peck came to head with Eastwood over a scene involving Eastwood offering a drink in a flask to the Sergeant Major; Peck stood his ground and insisted this scene was laughable. Eastwood eventually relented but the relationship between the producers continued to sour.[180] Within months, Manes was fired and Eastwood had rid of his best friend and producing partner, replacing him with David Valdes.[181] The film released in 1470 theatres, grossing a very respectable $70 million domestically.[182]

Eastwood's fifth and final Dirty Harry film, The Dead Pool was released in 1988. It co-starred Liam Neeson, Patricia Clarkson, and a young Jim Carrey. The Dead Pool, grossed $37,903,295, relatively low takings for a Dirty Harry film and was generally panned by critics. Eastwood began working on smaller, more personal projects, marking a serious lull in his career between 1988 and 1992. He directed Bird (1988), a biopic starring Forest Whitaker as jazz musician Charlie "Bird" Parker, a genre of music that Eastwood has always been personally interested in. Filming commenced in late 1987 and was shot in the old districts of Los Angeles, Pasadena and the Sacremento Valley, with additional New York City scenes shot in Burbank.[183] Bird was screened at Cannes and received a mixed reception. Spike Lee, a long term critic of Eastwood, the son of jazz bassist Bill Lee, and alto saxophonist Jackie McLean criticized the characterisation of Charlie Parker, remarking that it did not capture his true essence and sense of humor.[184] Critic Pauline Kael published a scathing review, confessing to loathing the film and describing it as "a rat's nest of a movie", which looks as if Clint "hadn't paid his Con Ed Bill".[185] Others, particularly jazz enthusiasts,[184] however, praised the music of the film and Eastwood received two Golden Globes—the Cecil B. DeMille Award for his lifelong contribution and the Best Director award for Bird, which also earned him a Golden Palm nomination at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was not a major commercial success. earning just $11 million. Eastwood, who claimed he would have done the film biography even if the script was no good,[186] was disappointed with the commercial reception of the film, later saying that, "We just didn't seem to have enough people in America who wanted to see the story of a black man who in the end betrays his genius. And we didn't get the support through black audiences that I'd hoped for. They really aren't into jazz now, you know. It's all this rap stuff. There aren't enough whites who are. either...".[187]

Carrey would later appear with Eastwood in the poorly received comedy Pink Cadillac (1989) alongside Bernadette Peters. The film is about a bounty hunter and a group of white supremacists chasing after an innocent woman who tries to outrun everyone in her husband's prized pink Cadillac. Pink Cadillac was shot in the fall of 1988 in the Rising River Ranch area and Sacramento.[188] The film was a disaster, both critically and commercially,[189] earning just $12,143,484 and marking the lowest point in Eastwood's career in years, causing concern at Warners that Clint had peaked and was now faltering at the box office after three unsuccessful films.[190] Pink Cadillac received poor reviews. Caryn James wrote: "When it's time to look back on the strange sweep of Clint Eastwood's career, from his ambitious direction of Bird to his coarse, classic Dirty Harry character, Pink Cadillac will probably settle comfortably near the bottom of the list. It is the laziest sort of action comedy, with lumbering chase scenes, a dull-witted script and the charmless pairing of Mr. Eastwood and Bernadette Peters." (New York Times, May 26, 1989.)

1990s

In 1990 he starred as a character closely based on the legendary film-maker John Huston in White Hunter Black Heart, an adaptation of Peter Viertel's roman à clef about the making of the classic The African Queen. The film was shot on location in Zimbabwe in the summer of 1989,[191] although some interiors were shot in and around Pinewood Studios in England. The small steamboat they used in the whitewater scene is the same boat Humphrey Bogart's character captained in The African Queen (1951). The film was closely based on the novel, although the ending was changed to the killing of an elephant, even though in Huston's memoirs An Open Book (1980) he had claimed to never have killed an elephant in his life and believed it was "a sin".[192] It received some critical attention but only had a limited release, earning just $8.4 million.[193]

Later in 1990, Eastwood directed and co-starred with Charlie Sheen in The Rookie, a buddy cop action film. Raúl Juliá and Sônia Braga play German villains engaged in an illegal luxury car theft operation. The film, shot in San Jose, California, features an unconventional female-on-male rape scene. Critics were unconvinced with the macho jiving between Eastwood and Sheen and improbable scenario, and believed that many of the actors were miscast.[194] Vincent Canby of The New York Times described the film as "astonishingly empty" whilst Glenn Lovell of the San Jose Mercury News strongly criticised what he called "blatant racial stereotyping", from the Hispanic car thieves, the Puerto Rican with a comic German accent to his Brazilian sex kitten bodyguard.[195] Released in December of that year, the film was a commercial success and earned a reasonable $43 million at the box office in the United States.[193] 1991 was only the third year in 20 years of Eastwood's career where one of his films didn't appear in the cinemas.[196] The reason for this was an on going law suit filed by Stacy McLaughlin, whose car Eastwood had rammed out of his parking space in the Malpaso parking lot.[197] In the end Eastwood was victorious but agreed to pay McLaughlin's court fees if she agreed not to appeal.[196]

Eastwood rose to prominence yet again in the early 1990s, rising above the lull in his career he had been experiencing for years, proving another benchmark in his career. In 1992, he revisited the western genre in the self-directed film, Unforgiven, taking on the role of an aging ex-gunfighter long past his prime. The film was written by David Webb Peoples, who had written the Oscar nominated film The Day After Trinity and also co-wrote Blade Runner.[196] The idea for the film dated as far back as 1976 and originally went under the titles The Cut-Whore Killings and for a much longer period during the 1980s ran under the title, The William Munny Killings.[196] The project was delayed, partly because Eastwood wanted to wait until he was old enough to play his character and to savour it as the last of his western films.[196] The film, also starring such esteemed actors as Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman, and Richard Harris and then girlfriend Frances Fisher, laid the groundwork for such later westerns as Deadwood by re-envisioning established genre conventions in a more ambiguous and unromantic light. Much of the cinematography for the film was shot in Alberta, Canada from August 1991 by director of photography Jack Green.[198] Production designer, Henry Bumstead, who had worked with Eastwood on High Plains Drifter, was hired to recreated the "drained, wintry look" of the Western.[198]

Unforgiven was a great success both in terms of box office and critical acclaim. Unforgiven earned between $13 and $14 million in ticket sales in its opening weekend, becoming the best-ever opening for a Clint film.[199] It eventually earned $160 million in ticket sales in the United States alone.[200] The critical reaction to the film was very positive. Jack Methews of the Los Angeles Times described the film as "The finest classical Western to come along since perhaps John Ford's 1956 The Searchers.[199] Hailed by many critics as one of the best films of 1992, Richard Corliss in Time wrote that the film was "Eastwood's meditation on age, repute, courage, heroism -on all those burdens he has been carrying with such grace for decades".[199] The film was nominated for nine Academy Awards,[201] including Best Actor for Eastwood and Best Original Screenplay for David Webb Peoples. It won four, including Best Picture and Best Director for Eastwood. Eastwood also garnered the Best Director Award from the National Society of Film Critics.[202] As of 2010, Unforgiven is the last western film that Eastwood has made.

In 1993, Eastwood played Frank Horrigan, a guilt-ridden Secret Service agent in the thriller In the Line of Fire, co-starring John Malkovich and Rene Russo and directed by Wolfgang Petersen. As of 2009, it is his last acting role in a film he did not direct himself. This film was a blockbuster and among the top 10 box-office performers in that year, earning a reported $200 million in the United States alone.[203] Later in 1993, Eastwood directed and co-starred with Kevin Costner in A Perfect World. Set in the 1960s, similar to Lonely Are the Brave, it relates the story of a doomed character purused by the state police using modern transportation and communication.[204] It grossed $31 million in box office receipts in the United States with overseas gross over $100 million, making it a financial success. The film received largely positive reviews, although some critics believed that the film at 138 minutes was too long. Janet Maslin of the New York Times believed the film was the highest point of Eastwood's directing career to date and remarked that "it gives real meaning to the subject of men's legacies to their children".[205] It has an 85% score on Rotten Tomatoes.[206][207] In the years since its release, the film has been acclaimed by critics as one of Eastwood's most underrated directorial achievements.[208] Cahiers du cinéma selected A Perfect World as the best film of 1993.

In May 1994, Eastwood attended the 1994 Cannes Film Festival and was presented with France's medal of the Comandeur de L' Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Jeanne Moreau commented, "Its remarkable that a man so important in European cinema has found the time to come here and spend twelve days watching movies with us".[209] On the jury at Cannes that year were also two people very familiar to Eastwood, Catherine Deneuve (with whom he had an affair with back in the mid 1960s) and Lalo Schifrin who had composed most of the jazz tracks to his Dirty Harry films.[209]

"The roles that Eastwood has played, and the films that he has directed, cannot be disentangled from the nature of the American culture of the last quarter century, its fantasites and its realities."

Eastwood continued to expand his repertoire by playing opposite Meryl Streep in the love story The Bridges of Madison County (1995). Based on a best-selling novel by Robert James Waller,[211] it relates the story of Robert Kincaid (Eastwood), a photographer working for the National Geographic who has a love affair with a middle-aged Italian farm wife in Iowa named Francesca (Streep). Eastwood and Streep got along famously during production and such was their on-screen chemistry that a number of people believed that the two were having an affair off-camera, although this has been denied by both.[212] The film was also a hit at the box-office and grossed $70 million in the United States.[213] The film, unlike the novel, surprised film critics and was warmly received. Janet Maslin of the New York Times wrote that Clint had managed to create "a moving, elegiac love story at the heart of Mr. Waller's self-congratulatory overkill", whilst Joe Morgenstern of the Wall Street Journal described The Bridges of Madison County as "one of the most pleasurable films in recent memory".[213] Eastwood directed and starred in the well-received political thriller Absolute Power. The film's ensemble cast featured Gene Hackman, Ed Harris, Laura Linney, Scott Glenn, Dennis Haysbert, Judy Davis, and E. G. Marshall. Eastwood played a veteran thief who witnesses the Secret Service cover up a murder the President was responsible for.

Eastwood directed Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which starred John Cusack, Kevin Spacey and Jude Law, based on the novel by John Berendt. Several changes were made from the book. Many of the more colorful characters were eliminated or made into composite characters. The reporter, played by John Cusack, was based upon Berendt, but was given a love interest not featured in the book, played by Eastwood's daughter, Alison Eastwood. The multiple Williams trials were combined into one on-screen trial. Jim Williams's real life attorney Sonny Seiler appeared in the movie in the role of Judge White, the presiding judge at the trial. Advertising for the film became a source of controversy when Warner Bros.used elements of Jack Leigh's famous photograph in its movie posters without his permission. The film received a mixed response from critics and has a 52% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times wrote, "I enjoyed the movie at a certain level simply as illustration: I was curious to see the Lady Chablis, and the famous old Mercer House where the murders took place, and the Spanish moss. But the movie never reaches takeoff speed; its energy was dissipated by being filtered through the deadpan character of Kelso."[214]

In 1999, Eastwood directed True Crime. Clint Eastwood plays Steve Everett, a journalist recovering from alcoholism, given the task of covering the execution of murderer Frank Beechum (played by Isaiah Washington). Everett discovers that Beechum might be innocent, but has only a few hours to prove his theory and save Beechum's life. The film was a large box-office bomb domestically, easily becoming his worst performing film of the 1990s.[215] It had an opening weekend gross of $5,276,109 in the US and grossed $16,649,768 total in the US, out of a budget of $55 million. It received mixed reactions from critics, with a score of 51% on Rotten Tomatoes. James Berardinelli wrote, "True Crime has the potential to be a truly memorable film, and, for more than three-quarters of its running time, it is poised to live up to that potential. But then there are the final twenty minutes, which proffer the almost-painful experience of watching compelling drama devolve into mindless action. True Crime's denouement is perplexing and exasperating, because, aside from generating some artificial tension, it contributes nothing to the story as a whole, and, consequently, serves only to cheapen it."[216]

2000s

In 2000, Eastwood directed and starred in Space Cowboys, which also starred Tommy Lee Jones, Donald Sutherland, and James Garner. In the film, he plays Frank Corvin, a retired NASA engineer called upon to save a dying Russian satellite. Space Cowboys was one of the year's commercial hits and was generally well-received and holds a 79% rating at Rotten Tomatoes. The film received a moderately favorable review from Roger Ebert who remarked, “it's too secure within its traditional story structure to make much seem at risk—but with the structure come the traditional pleasures as well... Eastwood as director is as sure-handed as his mentors, Don Siegel and Sergio Leone. We leave the theater with grave doubts that the scene depicted in the final feel-good shot is even remotely possible, but what the hell; it makes us smile.”[217]